This post explains what elliptic curves are and how they can be used to build an alternative Diffie-Hellman key exchange system called ECDH (Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman). In a previous post we introduced the original Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol based on modular arithmetic. We also saw how that protocol could be used as the basis of a PSI (private set intersection) protocol. We can also build a PSI protocol from ECDH, as we’ll see in a future post.

What is an elliptic curve?

An elliptic curve is a curve which satisfies an equation of the form

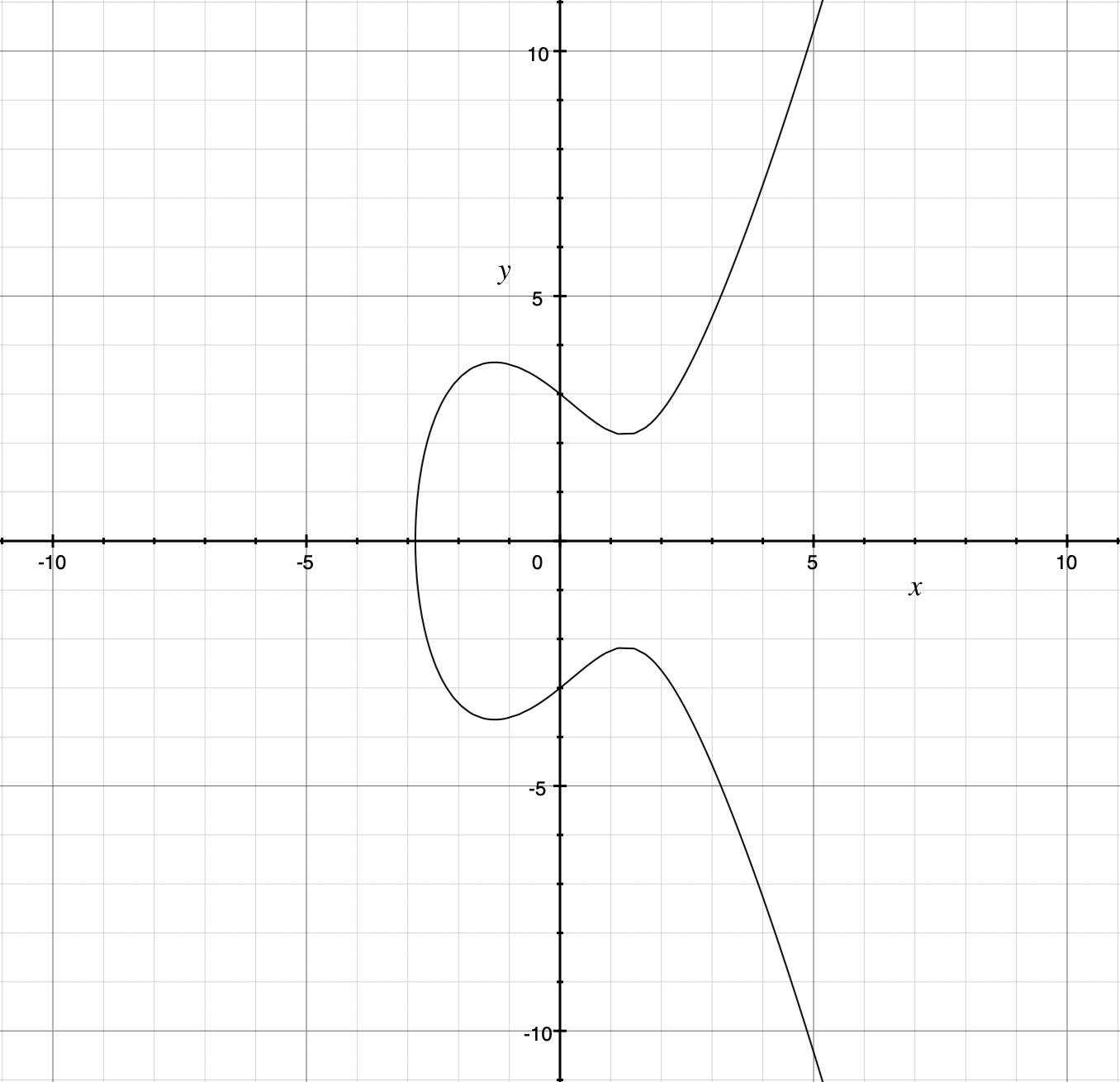

\[y^2 = x^3 + ax + b\]Depending on the values of \(a\) and \(b\) they can have some pretty weird shapes, but often they look something like this:

which is \(y^2 = x^3 -5x + 9\).

Here are a few important features of this curve (and other elliptic curves):

- It is symmetrical about the \(x\)-axis (because there are two roots of each positive \(y^2\) term).

- Not every \(x\) value has a corresponding \(y\) value (because there is no solution to the square root of a negative number).

- If you draw a straight line on this graph it will intersect the curve at three points (maximum).

Point addition and multiplication

Besides the above features, there are some special operations defined for points on elliptic curves. One of these is addition. If you take two points, \(P\) and \(Q\), on an elliptic curve, the result of adding them together is found like this:

- Draw the line which passes between \(P\) and \(Q\).

- Find the third point, where this line intersects the curve (if it exists).

- Reflect that point about the \(x\) axis to obtain the point \(R\), which also lies on the curve.

- \(R\) is the result of adding \(P\) and \(Q\).

Why is this called “addition”? At first glance it doesn’t look very much like addition in more familiar contexts (like integers or real numbers, for example). But it actually shares these important properties with those operations:

- It’s commutative, meaning it doesn’t matter if you add \(P\) to \(Q\) or \(Q\) to \(P\), the result is the same.

- It’s associative, meaning if you add three points \(P\), \(Q\), and \(R\) together, it doesn’t matter if you first calculate \(P + Q\), then add \(R\) or if you first calculate \(Q + R\) and then add the result to \(P\).

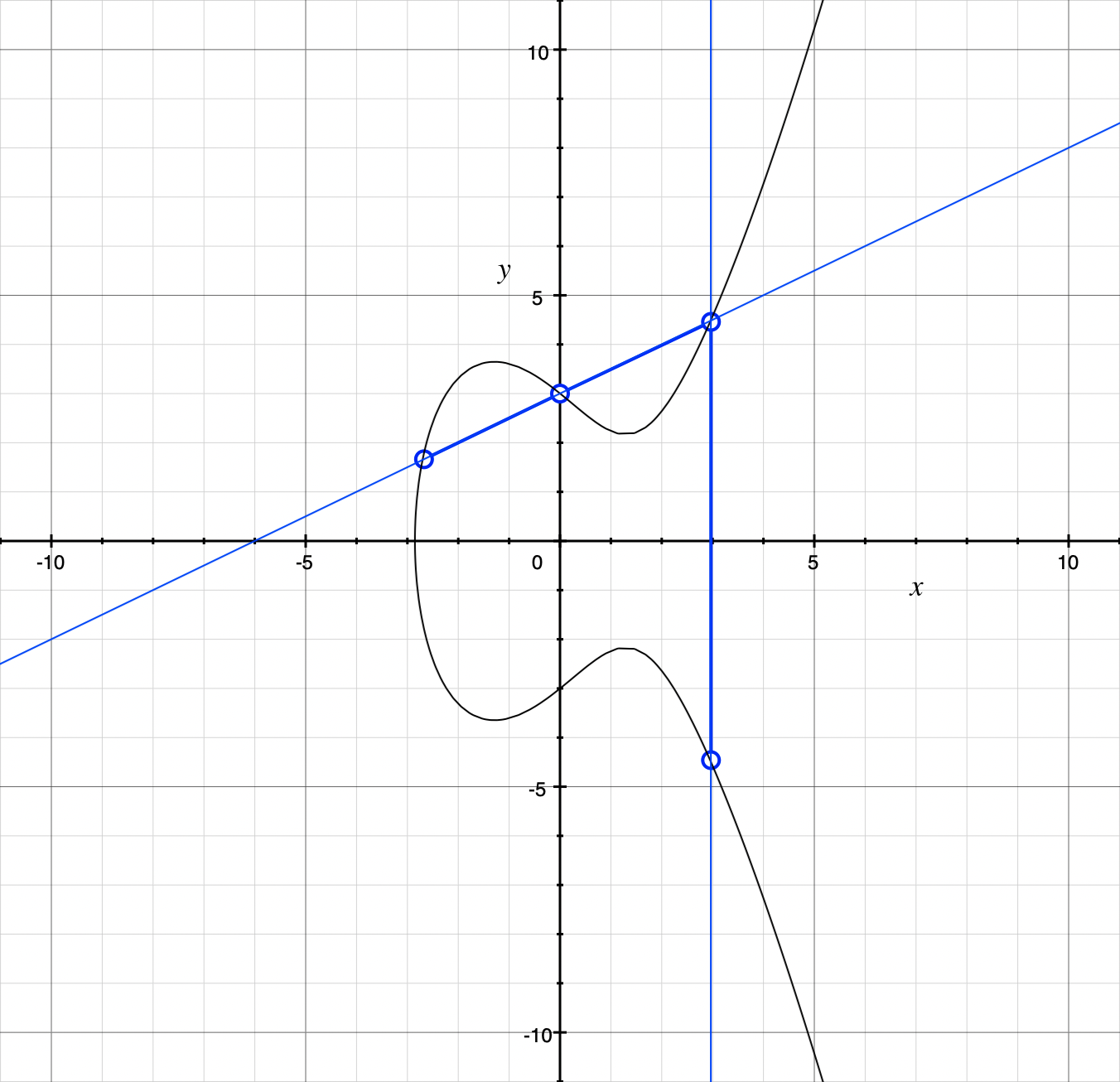

Here’s an illustration of how that process might look with the same curve as before:

Here we take points at roughly \((-2.7, 1.7)\) and \((0, 3)\) and the result of the addition is roughly \((3, -4.5)\).

What if we want to add a point to itself? If we only have one point, we aren’t constrained in how we draw a straight line through it, as we normally are with two points. So as a special case, adding a point to itself involves finding where the tangent of the curve at that point intersects the curve again, and then reflecting about the \(x\)-axis as usual.

Point multiplication

We can define multiplication of a point by a scalar via addition. So for a point, \(P\):

- \(P \times 1\) is just \(P\),

- \(P \times 2\) is the result of adding \(P\) to itself (as described above),

- \(P \times 3\) is found by adding \(P\) to the result of \(P \times 2\),

- \(P \times 4\) is found by adding \(P\) to the result of \(P \times 3\), and so on.

In practice there are more efficient ways of performing the calculation, but this method works.

Application to cryptography

In the illustrations above, the elliptic curves are defined over the set of real numbers, but for cryptographic purposes they’ll usually be defined over a finite field, such as the set of integers modulo some prime number. In that case, the curve will consist of a set of distinct points, rather than anything that would look like a curve on a graph.

For cryptographic purposes, it’s also important to mention the role of generators. In modular arithmetic, if \(g\) is a generator of a multiplicative group of integers modulo \(n\) then raising \(g\) to successive powers, \(g^1, g^2, ...g^{n-1} \mod n\), generates every value between \(1\) and \(n-1\). In the context of elliptic curves defined over a set of integers, if a point \(G\) on the curve is a generator of that curve then successively adding \(G\) to itself will hit all the other points on the curve and then eventually return to itself.

The key exchange problem and the shape of the solution

As before, Alice and Bob want to send encrypted messages to each other using a symmetric encryption scheme, so they need a shared secret key for encryption and decryption. How do they agree on a secret key without revealing it to Eve who is eavesdropping on all their communications?

Recall from the previous post that the key to solving the problem lies in finding two one-way functions whose composition is commutative. With the original Diffie-Hellman protocol, the solution is to use modular exponentiation, with two different (secret) exponents. But armed with elliptic curves we have another option.

The ECDH protocol

ECDH adjusts the standard Diffie-Hellman protocol to use point multiplication on an elliptic curve as its one-way function. I.e. if you have a point and a number, then we assume it is easy to multiply the point by the number. But if you only have the point and the result then we assume it is difficult to find the original number that point was multiplied by. And multiplication by two different numbers is commutative because you’re just adding a point to itself a bunch of times: what matters is the total, not how the additions break down. (Apparently these assumptions don’t hold anymore thanks to quantum computing, but ignore that for the purposes of this post.)

So here’s the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol using elliptic curve point multiplication instead of modular exponentiation:

- The protocol assumes Alice and Bob have agreed on an appropriate elliptic curve \(E\) and a point \(G\) which is a generator of that curve

- Alice randomly generates a private key \(a\).

- Alice calculates a new point, \(A\) on \(E\) by multiplying \(G\) by \(a\).

- Alice sends \(E\), \(G\), and the calculated point \(A\) to Bob.

- Bob randomly generates a private key \(b\).

- Bob calculates \(G \times a \times b\) by adding point \(G\) to point \(A\) \(b\) times.

- Bob calculates a new point, \(B\) on \(E\) by multiplying \(G\) by \(b\).

- Bob sends the calculated point \(B\) back to Alice.

- Alice calculates \(G \times b \times a\) by adding point \(G\) to point \(B\) \(a\) times.

Alice and Bob now know the point \(G \times ab\), and can derive a shared secret from it, for example by using the \(x\) coordinate of the point. Eve the eavesdropper has seen only \(E\), \(G\), \(A\), and \(B\). She is unable to derive the value of \(a\) from \(A\) or \(b\) from \(B\) efficiently without solving the “elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem” (analogous to the discrete logarithm problem we encountered in the post on the standard Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol). And without either of those values she is unable to calculate the secret key.

The advantage of ECDH over the standard Diffie-Hellman protocol is efficiency: using elliptic curves requires smaller private keys for the same level of security.

Code

I haven’t implemented all the maths for elliptic curves (yet!) but I have got a version of the ECDH protocol in my learning repository, using the elliptic package from npm.

WARNING: My library is not recommended for production use. It was written for learning purposes only.

Here’s how to use the code with the default P-256 curve (a controversial choice!):

const { Party } = require("./build/cryptosystem/elliptic-curve-diffie-hellman");

const alice = new Party(); // Generates a private key and picks a default generator for the curve

const bob = new Party(); // Generates a different private key but picks the same default generator

const { g } = alice.ec;

const aliceIntermediateValue = alice.raise(g); // I.e. multiply point g by Alice’s secret scalar

const bobIntermediateValue = bob.raise(g);

const aliceSharedSecret = alice.raise(bobIntermediateValue);

const bobSharedSecret = bob.raise(aliceIntermediateValue); // Same as aliceSharedSecret

Summary

In this post we’ve taken a look at elliptic curves, and how they can be used as an alternative basis for a Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol. Next time we’ll see how this can be developed into another PSI protocol.

Links

- Wikipedia article on ECDH

- Node.js implementation from my privacy learning repository